Science Is Not "Truth"

Our knowledge evolves, our methods improve, and that’s what makes science worth trusting.

I’ve spent my life in science — studying it, teaching it, and sometimes fighting against its misuse. That’s why I care so much about how we talk about it. My goal isn’t to undermine trust in science, but to give people a more accurate sense of what it really is and how it really works.

Oddly enough, one of the most pro-science things we can do is stop pretending that science is perfect. When we acknowledge its limits, its uncertainties, and even its failures, we make it stronger. When we oversell it as “the Truth,” we set it up to fail. And, that is what this week’s post dives into — why it rubs me the wrong way when some conflate science with “Truth.”

Here’s my take: science doesn’t hand us Truth with a capital T. It gives us provisional truths—models and explanations that work until better ones replace them. That’s not weakness; that’s the design.

Let’s explore!

1. When Good Science Gets Better — and “Truth” Changes

Some of the most important advances in history come not from fraud or mistakes but from refining the models we use to understand the world.

The Earth at the center of the universe.

For centuries, geocentrism wasn’t superstition — it was science. Ptolemy’s model explained the motions of the heavens well enough to guide calendars and navigation. Then Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler came along with new observations and mathematics, and the old “truth” crumbled.Bloodletting as medical treatment.

For centuries, physicians bled patients to rebalance their “humors.” George Washington’s final illness in 1799 was treated with multiple bleedings. At the time, this was mainstream medicine, rooted in theory and experience. Today, we recognize that it often hastened death rather than prevented it. [And yes, there are a few specific conditions where bloodletting is still used, but we won’t dive into those details.]The stress theory of ulcers.

For decades, ulcers were said to be the product of personality and stress. Patients were told to relax, change jobs, or avoid spicy foods. Then Barry Marshall and Robin Warren showed that Helicobacter pylori infection was the primary cause. Marshall famously drank a flask of the bacteria to prove his point.

It’s naïve to think we’ve finally reached the end of the road — that today’s science has given us the final answers. History should make us humble. We’ve been wrong countless times, and we will be wrong again. That doesn’t mean science is broken; it means it’s working. Every overturned idea is a step closer to reality.

2. When Two “Truths” Can Coexist

Not all controversies are black-and-white. Sometimes, honest studies with solid methods produce results that appear contradictory.

Coffee. Big cohort studies show coffee drinkers live longer. Smaller genetic studies show certain people process caffeine poorly and face more risk. Both are true — it depends on who you study.

Masks. Population studies show masks reduce viral spread. But results vary depending on mask type, fit, and context. A trial in one community might show no benefit, while another shows strong protection. Both reflect different conditions.

Exercise and heart biomarkers. After ultramarathons, athletes often show elevated troponin. Does that mean running harms the heart? Maybe briefly — but over time endurance training is protective. (I’ve studied this, so perhaps, I’ll write more on this separately in the future).

Here’s the issue: some people pick only the studies that fit their worldview (confirmation bias). Others flatten everything into false balance. Journalists often write, “There are studies showing X works, and studies showing it doesn’t,” as if both sides carry equal weight. But in science, not all evidence is created equal. A well-designed randomized trial is not on par with a small, poorly controlled study. Failing to weigh quality is just as misleading as ignoring evidence entirely.

3. When “Truth” Was Never True — Fraud in Science

The most corrosive cases are when what was presented as truth was fabricated. Fraud doesn’t just mislead scientists; it undermines the public’s belief in the entire enterprise.

The vaccine-autism scare.

Andrew Wakefield’s 1998 paper linking the MMR vaccine to autism wasn’t just flawed — it was fraudulent. He altered data, failed to disclose financial conflicts, and manipulated the story. Even after retraction, the damage lingers in vaccine hesitancy movements worldwide.The stem cell cloning scandal.

In the early 2000s, Hwang Woo-suk claimed to have cloned human embryonic stem cells. The announcement electrified the scientific community. But it was all fabricated, and when exposed, it set the field back and seeded public suspicion about stem cell science more broadly.Image manipulation in Alzheimer’s research.

A highly cited 2006 paper on the role of amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s included images later alleged to be fabricated. For nearly two decades, that work influenced billions of dollars in research investment. If the foundation was fraudulent, the ripple effects touch an entire field.

When fraud is exposed, people may conclude not just that a particular scientist lied, but that science itself is unreliable. That’s the collateral damage of treating science as “Truth.”

4. The Cost of the “Truth” Myth

Framing science as “the search for truth” creates three traps:

Truth changes.

When science updates itself, people feel whiplash and lose confidence.Truth can be conditional.

When two valid studies find different answers, nuance is mistaken for contradiction.Truth can be fabricated.

When fraud collapses, the whole edifice looks rotten, not just the bad apple.

The danger is that all of this can make science look untrue. The normal process of updating, refining, and sometimes correcting errors gets misread as deception. In other words, the very thing that makes science work — its ability to change — can make “Truth” appear to have been a lie all along. That perception is corrosive, both for science and for society.

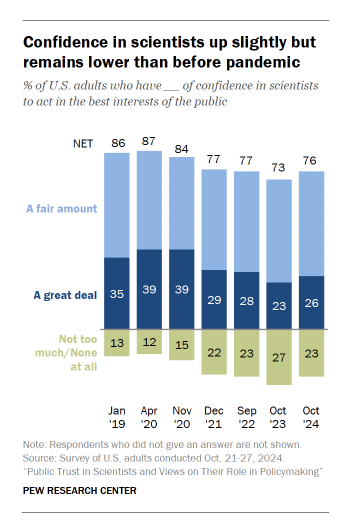

We do know that trust in science has eroded. Since 2021, Pew surveys show more than 1 in 5 American adults say their confidence in scientists is “not too much” or “none at all.” The chart I’ve included below shows the topline numbers, but the full report is even more revealing — especially the political divides in who trusts science and who doesn’t.

5. Why Exposing Bad Science Might Strengthen Trust

If you’ve read my other posts, you know I spend a lot of time digging into flawed studies, misleading claims, and outright fraud. Some people worry that pointing out how bad science can be only erodes public trust further. I see it differently.

Exposing bad science isn’t an attack on science — it’s an act of loyalty to it. By showing the flaws, biases, and occasional frauds, I’m not trying to convince people that science can’t be trusted. I’m trying to give people a more accurate picture of what science really is: not a binary of “trustworthy or not,” but a continuum.

Some research is robust, well-designed, and highly reliable. Other research is fragile, underpowered, or misleading. And yes, some is fraudulent. Recognizing those differences is essential to making sense of the scientific landscape.

In my opinion, If we stop pretending all science is equally true, then acknowledging flaws strengthens trust. The alternative — treating all science as a monolith — is what really damages confidence (again, my opinion). Because when one piece collapses, the whole structure looks suspect.

6. The Real Risk of Overselling Science

Think about the slogans we hear: “Follow the science.” “I believe in science.” These phrases are well-intentioned, but they package science as something far simpler than it really is. They don’t always mean “science is absolute truth,” but they do suggest that science provides a single, clear answer waiting to be followed.

The problem is that science rarely works that way. It’s messy, conditional, and evolving. Some questions yield robust, straightforward answers. Others remain unsettled, with competing models or context-dependent results. And, the path often changes as new data emerge.

When fragile or evolving claims are bundled with robust ones, any wobble is taken as proof the entire structure is untrustworthy. Vaccine trials, climate models, school masking policies, and nutrition epidemiology are not the same kinds of science. They carry different levels of certainty and different margins of error.

By acknowledging that continuum — that some areas of science are more straightforward and reliable, while others are uncertain and still developing — we actually build resilience. When one claim fails, people don’t lose faith in all of science. They see it for what it is: a process with stronger and weaker branches, not a single brittle pillar. And once again, that’s my opinion — not an evidence-based claim.

7. A Better Way to Talk About Science

Instead of promising Truth, we should promise process.

Science is:

The best explanation we have right now.

A system designed to update itself when new evidence appears.

A community effort where errors and fraud can be (eventually) caught and corrected.

That’s not as sexy as “the Truth.” It’s harder to put on a bumper sticker. But it’s also far more accurate — and it leaves room for growth rather than setting up disappointment.

If the public understood science as a refining process, then every change (regarldess of direction) would be seen as progress, not betrayal. Nuance would look like depth, not weakness. And fraud would be recognized as a violation of the system, not representative of the system itself.

8. Closing Thoughts

If we tell people science is the search for truth, every correction looks like a lie exposed.

If we tell them science is the search for better explanations, every correction looks like progress.

That difference might be the line between trust and cynicism in the years ahead.

Science chases truth, but it seldom fully catches it. What we hold today isn’t the final Truth—it’s the best version we’ve built so far.

What’s a time when your understanding of science shifted — whether in medicine, health, climate, or any other area?

Or, what’s your take on how we should talk about science to make trust stronger?

Share your experience — or anything else this post sparked for you — in the comments!

Excellent explanation on the distinction between science as a method of discovery and science as an institution that can't be questioned. Our understanding improves through continuous inquiry, but too many figureheads seem to expect blind obedience.

Great article, thank you. I particularly like this:

"Exposing bad science isn’t an attack on science — it’s an act of loyalty to it."

My thoughts exactly.

But there is a type of problem in science not mentioned here: Beliefs by influential scientists in something that has virtually no evidence, yet it's repeated so often that they and the press treat it as fact. Such beliefs are currently impervious to evidence. Is that science?

This is a serious problem in the epidemiology of developmental disorders including autism. Currently, anyone trying to do something about it is relegated to being a voice in the wilderness. We must fix that.