When the Same Data Tells Different Stories

A reflection on 3I/ATLAS, uncertainty, and the science of interpretation

There’s a new object drifting through our solar system—3I/ATLAS, only the third interstellar visitor we’ve ever detected. The images are grainy, the physics are fascinating, and the conclusions people are drawing from those images… well, they’re all over the map.

What interests me most is not what 3I/ATLAS actually is.

It’s what the debate around it reveals about how experts interpret uncertainty.

Right now, highly trained people are looking at the exact same data and generating completely different stories… and those are being further extrapolated by the media To me, is far more revealing than the object itself.

This is not really an astronomy story.

This is a story about what happens in science when certainty isn’t available yet—and how easily evidence becomes a mirror for our expectations.

The same data, different stories

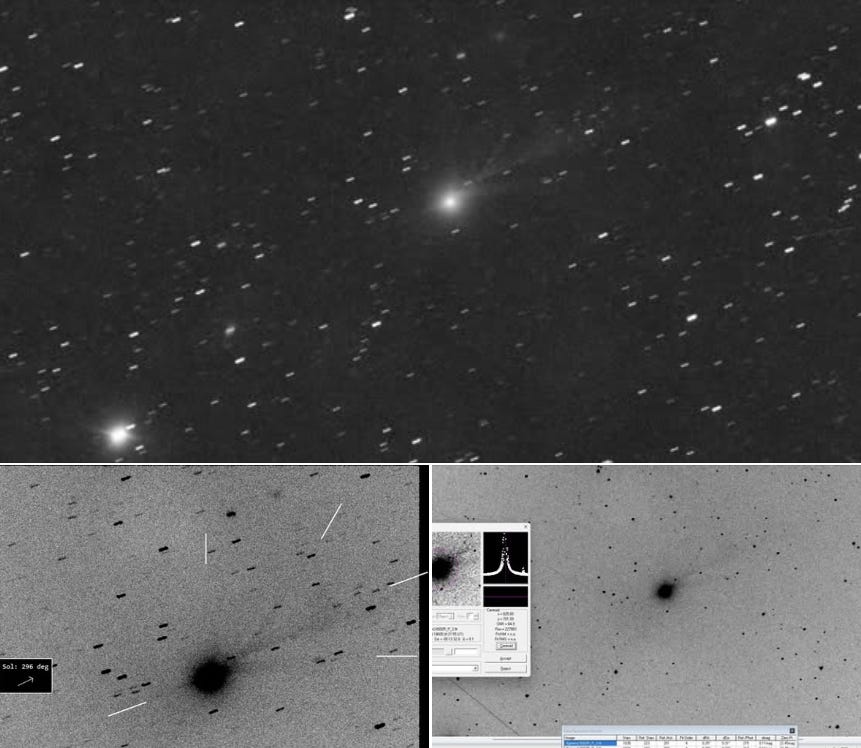

Look at the widely circulated early images of 3I/ATLAS, including this one from November 8 (from M. Jäger, G. Rhemann, E. Prosperi, via ICQ Comet Observations).

To comet specialists, these low-resolution smears show:

a distorted coma

asymmetric outgassing

rotational fragmentation

and behavior that seems strange only because we’ve observed so few interstellar objects

To others—particularly Avi Loeb and those influenced by his recent work—the same features can be interpreted as possible:

structural geometry

propulsion signatures

controlled motion

or engineered morphology

Here is what Loeb specifically writes:

“Is the network of jets associated with pockets of ice on the surface of a natural cometary nucleus or are they coming from a set of jet thrusters used for navigation of a spacecraft? We do not know. For now, let us enjoy the view. After all, a picture is worth a thousand words.”

This divergence isn’t about intelligence or education. It’s about broader interpretive frameworks.

One worldview says:

“This is a weird comet. We barely understand interstellar objects. Let’s gather more data.”

Another says:

“This is weird in a way that doesn’t fit expectations—maybe that means technology.”

Same photons.

Same pixels.

Different mental models.

What Loeb actually says (and what he doesn’t)

It’s also worth clarifying something that has already been distorted in the online discourse.

Avi Loeb is not saying that 3I/ATLAS is likely a spacecraft.

His public statements are far more measured:

It is “most likely a comet of natural origin.”

There are “anomalies worth paying attention to.”

On his “Loeb Scale,” these anomalies place the object at a 4 out of 10—still favoring a natural explanation.

We should collect more data

That’s a conditional scientific posture—not a declaration…

Loeb’s interpretation simply entertains a wider range of possibilities—including technological ones—than many comet specialists typically consider. Those specialists in comet morphology, dust–gas dynamics, and small-body physics say:

its irregularities are expected for an interstellar object

nothing so far requires extraordinary explanations

They are not dismissing ideas (or maybe some of them they are); they are interpreting the same images through their expertise.

Primary vs. surrogate outcomes

One way I’ve been thinking about this is through a medical lens.

In medicine, we distinguish between:

Primary outcomes — things we directly care about (e.g., heart attacks, survival)

Surrogate outcomes — biomarkers that suggest something but can’t confirm it (e.g., LDL cholesterol)

If aliens landed on Earth tomorrow, that would be a primary outcome.

Case closed.

But a strange shape in a low-resolution image from an interstellar object?

That’s a surrogate outcome—suggestive, intriguing, but several interpretive steps removed from any definitive conclusion.

Surrogate outcomes aren’t inherently bad—medicine uses them all the time—but they always require interpretation, and that interpretation is precisely where uncertainty creeps in:

Surrogate outcomes require judgment.

Judgment invites variation.

Variation leads to divergent narratives.

And that’s exactly what we’re seeing now.

A bright jet becomes a “thruster.”

Fragmentation becomes a “panel.”

Rotational irregularity becomes “maneuvering.”

Pixelation becomes “intent.”

The image below (source from Loeb’s Medium page) can’t directly tell us it’s alien tech, at best it’s a surrogate.

The same way a biomarker can masquerade as a clinical endpoint and be interpreted however one wants (which I have written about in JAMA Neurology regarding BDNF in brain injuries), a visual anomaly can masquerade as technology.

Optimism becomes inference.

Inference becomes certainty.

Why 3I/ATLAS became a Rorschach test

What’s interesting is that I posted a brief note on X pointing out the opposing interpretations of 3I/ATLAS, and someone replied:

“Science is not about opinions. It’s about data and the data, so far, says it’s artificial.”

I’m not pointing this out to mock the person—this comment reflects a very common misunderstanding about how science works: confusing the data with the meaning we assign to it.

The data don’t “say” anything. They’re just measurements — photons, pixels, flux values, noise. We are the ones who interpret them, and different frameworks lead to different conclusions.

That’s why it’s not surprising that interpretations split so quickly.

Several structural factors made this inevitable:

Interstellar objects are inherently weird.

With only ‘Oumuamua and Borisov as prior examples, we don’t yet know what “normal” looks like.Low-resolution imagery invites projection.

Ambiguity rewards imagination—in astronomy, medicine, biology, everywhere.Novelty amplifies bias.

Something from outside the solar system feels exceptional; exceptional things invite exceptional explanations.The incentives are skewed.

“Unusual comet” is interesting.

“Possible spacecraft” is viral.

These explanations spread differently in the public sphere—not necessarily because anyone is acting in bad faith, but because certain narratives naturally generate more excitement and attention.

These conditions guarantee divergent interpretations.

Where I personally land (with full humility)

I want to be abundantly clear:

I’m not an astronomer.

I’m not taking a side.

I’m not qualified to adjudicate comet morphology any more than an astrophysicist is qualified to weigh in on how blood hormone dynamics influence athletic performance.

What I am qualified to recognize is a familiar pattern: when data are new, limited, and exciting, people bring different interpretive frameworks to the table.

If I had to bet—strictly as an outsider—I’d guess 3I/ATLAS is a particularly interesting, highly unusual comet. Not because the alternative is impossible, but because in science we usually start with the simplest explanation that fits the data. And with only two prior interstellar objects in our history, almost anything can feel anomalous.

But this is just a guess.

And the worst outcome of being wrong about alien technology is… someone telling me a veterinarian-turned-physiologist misidentified a spaceship.

I can live with that.

Rare ≠ suspicious

One misconception worth addressing:

On Earth, “one-in-a-million” feels synonymous with “basically impossible.”

But in a universe this vast, one-in-a-million (or rarer) events are inevitable.

Interstellar space produces a staggering range of outcomes—perhaps most of which we’ve never seen.

So when 3I/ATLAS behaves strangely, that may reflect:

the diversity of interstellar formation environments

the rarity of our observational window

or simply our lack of experience

“How weird is too weird?” is the wrong question.

The right one is: “What range of behaviors should we expect when we have only two previous data points?”

When framed that way, surprise becomes the baseline expectation.

The loudest story isn’t always the best one

Most people will never view 3I/ATLAS through a telescope, and that’s completely normal. We rely on others to interpret specialized information for us. But in that process, something predictable happens: the explanations that spread the fastest are often the most dramatic, confident, or narratively satisfying.

This isn’t a criticism of curiosity.

It’s a reminder that:

charismatic communicators often simplify

pop-science culture rewards certainty

and ambiguity invites confident narratives long before the evidence is complete

When something extraordinary shows up in the sky, people want a story. That instinct isn’t a flaw—it’s the same instinct that drives us to learn. But it does mean that spectacular interpretations can outrun careful ones, especially with an object this new, this rare, and this mysterious.

I was going to post some of the overzealous, misleading headlines, but

already did a great job at this, so check out his article about it “Why 3I/ATLAS Needs to be a Spaceship.”Conclusion: The real story isn’t 3I/ATLAS — it’s interpretation

We may eventually learn what 3I/ATLAS is.

The data will mature.

The ambiguity will shrink.

The competing narratives will collapse into one.

For now, though, this moment reveals something more universal:

how experts interpret incomplete data

how priors shape perception

how ambiguity produces divergent stories

and how both overconfidence and over-dismissal arise from the same uncertainty

This happens in every scientific field—from astrophysics to medicine to biomechanics. 3I/ATLAS is just the newest example, with a little more cosmic dust and a lot more imagination.

Uncertainty isn’t a flaw.

It’s the starting point of science.

And right now, 3I/ATLAS is reminding us that data don’t interpret themselves.

People do.

And the way we interpret them says more about us than about the object lighting up our newsfeeds.

And honestly, it’s refreshing to see the internet arguing about coma morphology in a distant interstellar object instead of whether Taylor Swift is Travis Kelce’s good-luck charm.

Postscript — and a preview of tomorrow

Tomorrow (November 20) I’m publishing a short companion piece that explores the same theme from a very different angle. It involves a highly technical image analysis.

If you’re interested in how easily scientific vocabulary can shape our interpretation of ambiguous data, you won’t want to miss it.

Once that is published, I will link it to this. Stay tuned!

Thoughts? What’s your read on the 3I/ATLAS debate — and what does it remind you of in your own field? Let me know below.

James, you asked readers what does this remind us of in our own fields. I have something here.

You wrote: "Not because the alternative is impossible, but because in science we usually start with the simplest explanation that fits the data."

Yes, that's the way it's supposed to work.

But in my field, autism epidemiology, the bulk of public comments by scientists show a strong belief in an interpretation of the data that defies both logic and the data itself. And this is about actual outcomes, not just surrogate outcomes.

And, simultaneously, conspiracy theorists also interpret the data incorrectly to support their own beliefs.

Very few people are making public statements positing an explanation that actually fits the data.

The issue? The data clearly show a strong rate of increase in autism incidence. (Incidence is not prevalence.) You won't find that summary in the journal literature, nor in conspiracy theories. But it's right there in front of everyone.

And — this is Chapter 1 basic epidemiology — increasing incidence means something had to change to cause it. That is also being ignored.

We need more scientists to step up to the plate and be objective about what the evidence shows.

When the odds are astronomical, predictions become problematical.

If a Something can happen only once in a billion tries, but if you try a billion-billion times, the chance of witnessing the Something occurring go from near zero to nearly 100%.

Eventually, it seems all lotteries are won by somebody, assuming they are not stopped by the lottery makers.

Meanwhile, you're too right. Speech properly laced with esoteric jargon can sound convincing -- especially when we want it to be true.