The Most Popular Study I’ve Ever Published (And the Strangest?)

The story behind the science that gripped the world — one weiner at a time

Authors Note: This is the first post in a multi-part series about the backstory and unexpected impact of my most talked-about research study. Along the way, I’ll explore what it reveals about research culture, science communication, and the strange dynamics of going viral in academia.

It was the summer of 2020, and the world was deep in pandemic mode. We were glued to infection counts and hospitalization charts. The only conversations I had outside of teaching involved masks, vaccines, or wondering when this would all be over. Then, right in the middle of that information overload, I published the most successful paper of my career.

I didn’t discover a COVID cure. I didn’t develop a ventilator innovation or decode an antibody. I modeled the physiological limits of competitive hot dog eating.

You might’ve seen the New York Times headline, or heard me on NPR’s 1A. Maybe you read the article itself — Modeling the maximal active consumption rate in humans: perspectives from hot dog eating. But what you probably don’t know is the story behind the story — how it started, how it got published, and why this scientifically absurd idea exploded across the globe.

The Hot Dog Abstract

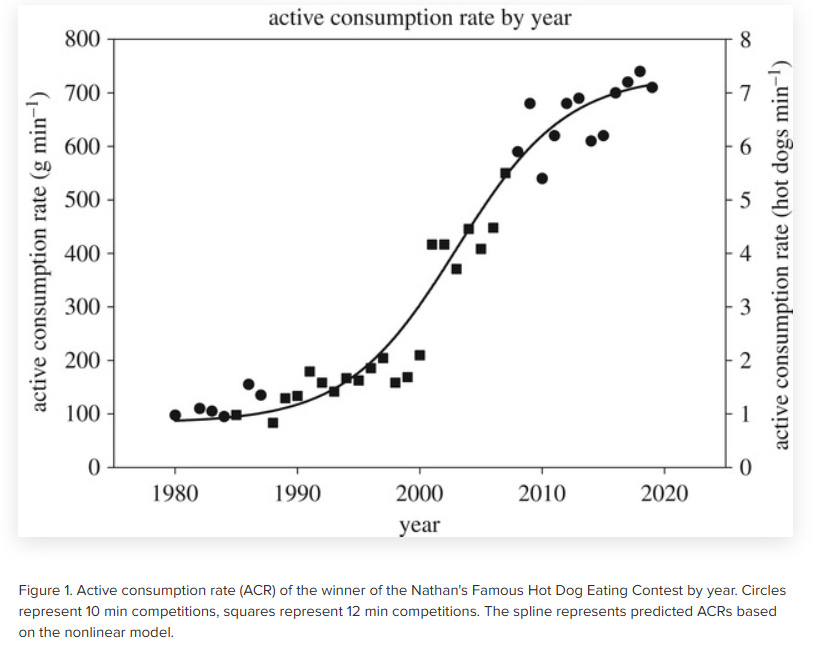

In July 2020, Biology Letters published my paper on the theoretical limits of human hot dog consumption. The idea was simple: I collected historical data from the Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest, modeled it mathematically, and estimated the maximum number of hot dogs a human could ever eat.

For those unfamiliar, the Nathan’s contest is held annually on the Fourth of July at Coney Island. It started in the 1970s as a local curiosity and slowly built a cult following. In the early years, winners ate 8–10 hot dogs in 10 or 12 minutes. By the 1990s, that number had crept into the 20s thanks to competitors like Ed Krachie and Mike DeVito.

Then everything changed in 2001.

That year, Takeru Kobayashi, a professional eater from Japan, entered the scene. In his debut, he broke the world record in the first five minutes, downing 25 dogs. By the time the 12 minute contest was over, he finished 50 hot dogs — doubling the existing record. ESPN coverage followed, and a new era of competitive eating was born. By 2018, Joey Chestnut was the reigning king, with a record of 74 hot dogs in 10 minutes.

From Track Meets to Meat

My academic background isn’t in food studies or gastrointestinal medicine — it’s in human performance (or at least, that’s one of my backgrounds, long story for another time). I’ve always been interested in the physiological limits of athletic feats. Years before the hot dog paper, I had engaged with debates in the sports science community over topics like sub-2-hour marathons and 100-meter sprint ceilings.

One day, while thinking about progression trends in elite sport, I had an idea: “I wonder if the hot dog eating contest follows a sigmoidal performance curve too?”

That single thought launched the project. But, that wasn’t the only reason that I did the study. In truth, part of the motivation was also personal curiosity. I wanted to see what would happen if I published a scientifically rigorous — yet inherently ridiculous — study. Would it go viral? Would the media bite? It was, in a way, a self-aware experiment in science communication: How much attention could a fringe but well-executed idea attract in a world saturated with serious headlines?

Using historical data (identified starting with Wikipedia links and then painstaking verified through archived news stories), I built a dataset and modeled it using Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) theory. GEV models are common in climate science — they estimate extreme outlier events, like a “100-year flood.” But they’ve also been used to estimate peak athletic performance, such as record-breaking sprints, long jumps, and horse racing performances.

The hot dog contest followed the same pattern: a slow rise in performance, a sudden acceleration (Kobayashi), and a plateau as competitors neared physiological limits. The math suggested the maximum number of Nathan’s hot dogs a human could eat in 10 minutes was about 83.5.

Confirming the Wiener Science

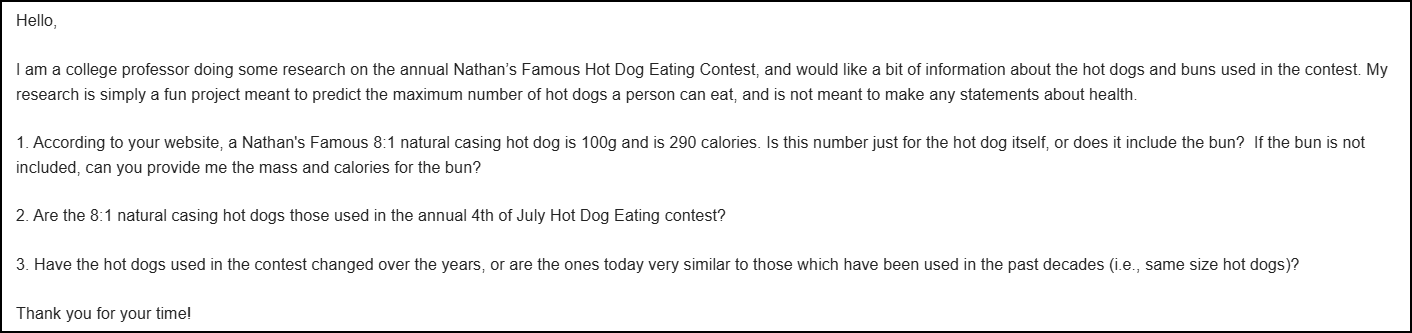

I didn’t want any room for doubt, so I reached out to Nathan’s Famous to confirm whether their hot dogs and buns had changed over time.

Here’s the original e-mail, sent in March 2019:

To my delight, the Director of Purchasing replied and assured me the formula had remained consistent.:

The information on the nutritional page of our website is for the hot dog and bun. The 8:1 Natural Casing hot dog is the one that is used in the contest. The hot dog is essentially the same hot dog that has been proudly served in our restaurants for the past 103 years.

This might seem like an odd detail to care about, but in a scientific model, especially one involving digestion, things like water content, density, and texture matter. Even minor changes in formulation could affect swallowing and stomach volume.

That’s why I specified “Nathan’s hot dogs” throughout this post. No, I’m not receiving any funding from Big Wiener. I just didn’t want anyone confusing it with backyard barbecue data, since not all dogs are created equal. The results might be completely different if we used Oscar Myer, Ball Park, Hebrew National, etc.

(And for the record, I’m a Jersey native — if given the chance, I prefer a Windmill hot dog. Ask anyone from the Shore.)

Going Beyond the Bun

As I worked through the study, I realized it needed something more. So I explored two additional questions.

First: How did humans stack up against other species? I reviewed literature on consumption in wolves, bears, and coyotes. Turns out, competitive eaters outperform bears and coyotes — at least in research-grade eating metrics. One inspiration came from the event in which Kobayashi challenged a bear on TV (no joke, watch the video and see who won!).

Second: Was there evidence that hot dog eaters improve their performance over time through eating-specific training? I tracked down individual competitor data and found that yes, repeat contestants tended to improve across years. In other words, there’s a measurable training effect in hot dog eating. It’s not just a stunt — it’s “athletic” performance.

Sending It Out Into the World

I decided to submit to Biology Letters. It felt like the right home: they had a reputation for publishing quirky but rigorous studies, and more importantly, their media team was excellent at promoting novel research. Timing mattered too — I knew The BMJ Christmas issue might love it, but their review process wouldn’t start until late summer, and if accepted, the Holiday season timing wouldn’t be idea.

So, I submitted the first version of the hot dog paper in April 2019 — a year before most of the public had ever heard of coronoviruses.

Then came the waiting game—peer review, revision, resubmission. One reviewer made a fascinating point: the hot dog record had increased over 700% since the contest began, while marathon and sprint records had improved by only ~50%. So I expanded the paper’s discussion of training, adaptation, and performance gains. The top eaters were arguably more dominant

Finally, in June 2020, after 14 months, including three rounds of review, I got the acceptance email. The publication date was set for July 14.

Hot Dogs Go Global

I was bummed by the mid-July release—it missed the 4th of July buzz. So I reached out to journalist Christie Aschwanden, whom I’d worked with before on a story about the Q-collar. She’s a pro — super smart and science-literate. She liked the paper and began asking questions.

On July 8, she casually mentioned she was writing it up for The New York Times.

That’s when it hit me: this was going to be big.

The article ran the same day the paper was published. And from there, the media frenzy began: Science Magazine, CNN, FOX News, Newsweek, Sports Illustrated, and dozens of others. Everyone wanted to talk to me. Some interviewed me seriously, and others were more focused on how many hot dogs I thought I could eat (answer: probably 8).

Even NPR’s Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me! featured my study as a trivia question. It was surreal. One day, I was creating asynchronous videos for my cardiovascular physiology class. The next, I was explaining bun hydration and swallowing mechanics to a swam of news reporters.

Coming Next:

In Part 2 (now available!) and Part 3 (coming soon, if Part 2 is popular), I’ll dig into more about the study, including the public’s reaction — why some questioned the idea of “wasting time” on hot dog research during a global crisis, and what it says about how we value different kinds of science. Subscribe today (for free!) so you don’t miss it, as well as my other insight into science, research integrity, and academic culture.

The uncanny timing of this study’s release—more than a year after submission—almost feels like a plot twist! Your clarity with statistics and commitment to transparency made it a pleasure to read.

Having spent time in pharmaceutical research before moving into health care, I recognize the long arc of discovery and the patience it demands. But it’s also a reminder of how easily public perception can be shaped—or skewed—by the randomness of timing and the mixed approaches of media framing. The assumptions made by the public—and often manipulated by the media—reveal a hidden vulnerability in public awareness. It’s easy to see how myths and misconceptions fuel the broader trend of disinformation in today’s discourse.

How do we keep science both accurate and accessible without losing the magic—or the message?