I keep seeing posts on Substack about how important sleep is — and they’re right. But what’s often missing from the conversation is the history of how we know sleep is absolutely vital. Some of the most striking animal studies on sleep deprivation are rarely discussed, and they reveal something we sometimes overlook: sleep is not just restorative, it is a requirement for life.

There’s good reason that I teach my Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) students about sleep, because it really is that important for every patient they encounter. Athletes need it to optimize training, recovery, and game-day performance. Patients need it to heal after surgery or illness. And ironically, when people are hospitalized — at the moment their bodies need sleep most — it’s often interrupted.

Since Beyond the Abstract is all about the behind-the-scenes of science, there’s another layer worth acknowledging: the ethics of this research. The classic weeks-long sleep-deprivation experiments were cruel by today’s standards, yet they produced some of the clearest evidence that sleep is essential for survival. I won’t go into the ethics in detail here, but I think they’re part of the story — and a reminder that science is rarely simple.

Sleep as a Requirement for Life

In this week’s video, I walk through the classic animal studies on sleep deprivation — from 1890s puppies to 1980s rats — and what they showed us about the absolute necessity of sleep. If you’ve only ever thought of sleep as a performance enhancer or a lifestyle factor, this history may surprise you.

A quick clarification before you hit play: the studies I’m talking about here involve total, extreme sleep deprivation — animals literally kept awake until they died. This is very different from the kind of sleep loss most of us experience. Missing a few hours will make you groggy, irritable, and less sharp, but it won’t kill you… not directly at least.

And on a more personal note, this post is something new for me — it’s the first time I’ve shared a video post here on Substack. I’ll still be writing as usual, but I thought this history of sleep research was worth telling on camera. I’ve actually been making videos just like these for my DPT students, since we went into COVID lockdown in 2020. I’ve gotten great feedback from them, so I am hoping that you like my style of video explainers as well!

A Closer Look: The Disk-Over-Water Studies

The most famous (and arguably most unsettling) sleep deprivation experiments were carried out in rats at the University of Chicago in the 1980s. The setup became known as the disk-over-water method. Here’s how it worked:

Rats were placed on a motorized disk suspended above a shallow pool of water.

When the experimental rat began to drift toward sleep, the disk rotated, forcing it to move — or risk falling into the water.

A “yoked” control rat was tethered to the same disk. This meant it also had to walk whenever the disk rotated, but it was still able to sleep when the experimental rat was awake.

The design made it possible to tease out the effects of sleep deprivation from other factors like stress or exercise. The conclusion was stark: even with food and water freely available, rats deprived of all sleep died within 2–3 weeks. When deprived only of REM sleep, they lasted a little longer — but still died from sleep deprivation.

If you’re curious about the details of the methods, here’s one of the original publications (Everson, Bergmann, & Rechtschaffen, Sleep, 1989).

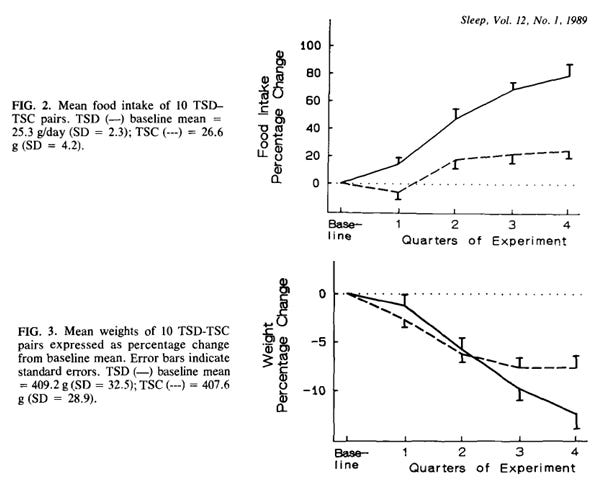

I won’t get into all of the results here, but sleep deprivation had major metabolic effects, causing the sleep deprived rats (lableled TSD in figure below) to eat more, yet lose weight, compared to their yoked-controls (labeled TSC below). The full-text paper behind these studies is linked here.

If you want to see a modern version of rodent sleep deprivation systens, below is a short video of a current sleep deprivation unit using a similar method. It’s a bit eye-opening to watch: the rat is repeatedly knocked off balance as the bar spins. Pro tip: listen with the volume on — the mismatch between the harshness of rats being knocked around and the generic upbeat soundtrack almost makes it more surreal.

Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

The takeaway from these studies is clear: without sleep, survival itself becomes impossible. While these studies represent extreme sleep deprivation (far beyond that experienced by most people) they definitely show sleep is absolutely essential for normal physiology… thus survival.

The implications of healthy sleep habits go far beyond laboratory animals.

For clinicians: Sleep isn’t just “nice to have.” It determines whether tissues heal properly, whether immune responses stay balanced, and whether recovery is delayed or derailed. Ignoring sleep is ignoring physiology. Much as many clinicians now make recommendations regarding exercise and nutrition, sleep should also be part of the discussion.

For athletes: Every rep in the gym, every hour of training, and every recovery strategy is amplified or undermined by sleep. You can’t “out-train” sleep deprivation.

For patients: Hospitals are paradoxical environments — the place where healing should be maximized, yet where sleep is constantly interrupted. We need to rethink how we treat rest as part of care.

A Note on Ethics

The history of sleep research also forces us to sit with uncomfortable truths. The early dog experiments — and even the later rat studies — were undeniably cruel. Yet they remain some of the most convincing demonstrations of sleep’s necessity.

This is a recurring theme in science: knowledge that feels indispensable to us today often came from methods we would (and should) reject now. Acknowledging that complexity doesn’t undermine the science — it makes us better at seeing the full picture of how knowledge is created.

Recipe for ClickBait

It would be easy to frame these studies with splashy, oversimplified headlines. I could have gone with:

“How a Few Sleepless Nights Will Kill You,” or…

“Want to Send Your Metabolism Into Overdrive? Get Less Sleep!” or… even

“Want to Eat More and Still Lose Weight? Try Sleep Deprivation!”

Each of those has a grain of truth. In the rat experiments, for example, the animals really did eat more while wasting away. But the headlines would miss the larger point. They take something nuanced — and already unsettling — and flatten it into something misleading.

I’m not saying anyone has actually spun these particular studies this way. My point is that it would be easy to do, and that’s often how science ends up in the public sphere: complex research translated into bite-sized “facts” that don’t capture the messy reality.

That’s exactly what I’m trying to unpack here on Beyond the Abstract. Not to make science sound simpler than it is, but to show why the nuance matters. Because the real story — that sleep is so deeply tied to metabolism, immunity, and survival that animals literally die without it — is more compelling than any headline.

Closing Thoughts

Since May, I’ve been aiming to post here every week. To hit that goal this time, I ended up working on this one past midnight — which, yes, is a little ironic for a post about the dangers of not getting enough sleep. Consider it an unplanned personal experiment (and one I don’t intend to repeat).

The bigger point, though, is this: sleep is not an optional luxury. Like air, water, and food, it’s woven into the fabric of life itself.

If you’d like to see more of these explorations — connecting physiology, research integrity, the quirks of academia, and the occasional dose of sports science — I’d love for you to subscribe. It’s free, and every new post and video will land right in your inbox.

I’d love to hear your thoughts. How do you think about the role of sleep in your own life or patient care — whether that’s training, recovery, or just day-to-day functioning? And what do you make of these classic animal studies: are they an indispensable part of science, or too unsettling to justify? Share in the comments — I always enjoy learning from the perspectives readers bring to these questions.