Science is self-correcting... Except when its not.

What happens when you actually try to fix the scientific record

If you spend any time around science, you hear the phrase constantly.

Science is self-correcting.

It shows up in lectures, editorials, and op-eds defending the credibility of research. It’s offered as reassurance when something goes wrong — when a study fails to replicate, when a claim collapses under scrutiny, when a headline turns out to be overstated. Yes, mistakes happen, the argument goes, but the system is built to catch them.

Peer review exists to identify errors before publication.

Post-publication critique exists to address problems that slip through.

Journals publish letters, corrections, expressions of concern, and retractions.

Replication weeds out the rest.

Over time, the truth rises.

The literature isn’t static; it’s meant to be revised as new evidence emerges or old analyses fall apart. Self-correction is the design feature we point to when defending the whole enterprise.

This idea isn’t crazy. In principle, it’s how science is supposed to work.

But design and reality aren’t the same thing. I know, I’ve tried to correct the literature… and failed.

I’ll share some of my experiences here.

Self-Correction ≠ Automatic ≠ Easy ≠ Fast

Correction doesn’t happen automatically. It requires

People to notice problems

Those people to invest time in documenting them, and then

Journals to act.

Journals have their own incentives. They are not just neutral stewards of truth; they are also brands with reputations to protect. Admitting that something published under your masthead is deeply flawed is not a cost-free act. It raises uncomfortable questions about editorial oversight and peer review quality.

In other words, there is a built-in conflict of interest. For concerns to be formally recognized, the same editorial team that allowed a paper to be published has to admit there was a problem in the first place.

Yes, yournals can correct the literature — and it happens regularly. But they also have reasons not to — especially when the error is embarrassing, inconvenient, or not yet impossible to ignore.

So yes, sometimes science does correct itself. High-profile failures get scrutinized. Egregious mistakes eventually surface. Fraud, when undeniable, is addressed.

But there are many ways for things to remain uncorrected without anyone behaving dishonestly or maliciously. A problem or major flaw can be real and well-documented and still be deemed too small, too niche, or too low-priority to fix. A critique can be accurate and still go unpublished. An interpretation can be misleading and still persist because it’s already escaped into the world.

I didn’t fully appreciate how wide that gap between design and reality was until I tried, twice, to push the system in the direction it claims to want to go.

Let’s go back to 2014 and see some of my attempts to address issues in the literature.

Running Low On Evidence

The first episode started with something relatively small. Not a controversial trial. Not a high-profile paper. Just a patient education page in JAMA about running injuries.

I opened it out of idle professional curiosity. My PhD is in Sports Medicine and everything running is what I love to study… It shaped my career pathway, and I know the literature well.

As I read the article about “running injuries” I was… shocked. This felt more like a fitness magazine article than a peer-reviewed article in one of the world’s most prestigious journals. Check it out, this doesn’t seem like anything groundbreaking:

But, the content was dated in a way that was hard to miss if you worked in the area. Ice. Anti-inflammatories. Rest. Broad, catch-all guidance that treated all running injuries as if they were slight variations on the same theme.

Then I hit the phrase “Achilles tendonitis.” That one word told me exactly how old the conceptual framework was.

By that point, for more than a decade, we’d been teaching students that most chronic Achilles problems aren’t inflammatory at all. They’re degenerative tendinopathies. For example, this 2012 systematic review describes how “repetitive stimuli load the tendon beyond its physiological tolerance leading it to degeneration” (and references a paper from 2000). Tendonitis? That’s so 1989.

Calling it “tendonitis” isn’t just semantics. It pushes clinicians and patients toward anti-inflammatories and away from loading-based rehab, which is actually what helps. Yes, that literature is nuanced, but telling a runner with a case of Achilles tendionpathy to RICE was far from the best clinical recommendation at that time of publication.

As I kept reading, the page bundled together running injuires into one big catch-all… Stress fractures, iliotibial band pain, muscle strains, and tendinopathies as if they were interchangeable inconveniences. Anyone who has worked with runners knows how misleading that is. A low-risk tibial stress reaction and a high-risk femoral neck stress fracture do not live in the same universe of management. One is “back off and modify.” The other can become an orthopedic emergency if you miss it.

None of this was cutting-edge controversy. This wasn’t esoteric physiology or some unresolved debate. It was the kind of basic clinical distinction we teach first-year DPT students.

What bothered me most wasn’t that it was simplistic. Patient pages are supposed to be simple. It was that it was wrong in ways that could actually matter. It was misinforming patients, and potentially clinicians.

But because it was JAMA, it carried an implicit authority. If something appears there, clinicians assume it’s been vetted. Patients assume it’s reliable.

So I did what I’ve always told trainees to do when they notice something off. If you see an error in the literature, you try to fix it.

I reached out to two colleagues — both experienced sports-medicine physical therapists. One of which literally wrote books on orthopedic injury diagnosis. The other had a DPT and PhD and advanced fellowship training. I’m not trying to play the “authority” card, but this was not our first rodeo.

We drafted a letter in accordance with JAMA guidelines. We cited the evidence, explained the terminology, suggested clearer distinctions between injuries. It wasn’t accusatory. We weren’t trying to embarrass anyone. We were just trying to make the handout more accurate for the people who would use it, and explain why our critique mattered.

We submitted it.

About a month later, a decision email arrived in my inbox.

I opened it expecting reviewer comments.

Instead, the message explained that the letter had not been sent out for peer review. It was being declined because it was considered low priority.

That phrase stuck with me — low priority. Not incorrect. Not unconvincing. Just… not important enough to take up space. Something unworthy of a URL.

In the grand scheme of everything JAMA publishes (cancer trials, global health crises, major policy debates) maybe a patient page about running injuries really was trivial. But that was the uncomfortable part. If even obvious, fixable inaccuracies didn’t merit correction because they were “small,” then what exactly did self-correction mean?

The handout stayed exactly as it was. Anyone who printed it the next day would get the same outdated advice.

Science hadn’t corrected itself. It shrugged.

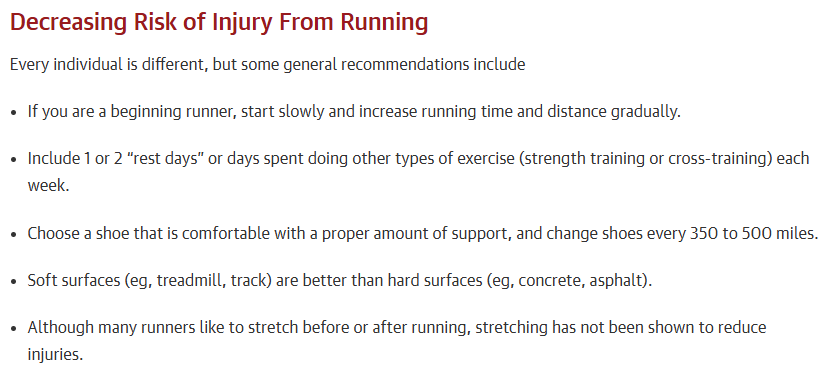

Over a decade later, it looks like it has received plenty of media attention (see Altmetric below)… The article has been veiwed over 200,000 times… And we wonder why outdated ideas die hard.

A Study Designed to Fail

The running study was not an isolated incident.

In 2014, JAMA Internal Medicine published a study on resveratrol, the antioxidant found in red wine. At the time, resveratrol was enjoying a kind of celebrity status. Supplements were popular. Articles about the “French paradox” and the benefits of a nightly glass of wine were constantly circulating. It was the next miracle drug.

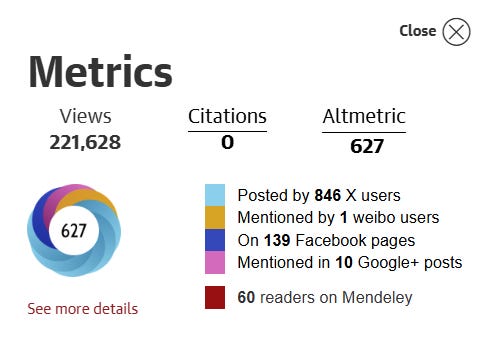

So when the paper concluded that resveratrol didn’t seem to improve cardiovascular outcomes, it got immediate media attention.

I saw it in Forbes. Then CBC. Then a string of other outlets. The headlines were decisive: the antioxidant in red wine doesn’t help your heart after all.

The story had a nice, clean narrative arc. A health fad debunked. Journalists love that… perhaps as much as they love promoting a new health fad. (See the 2015 ESPN article about red wine baths, elegantly captured in the image below.)

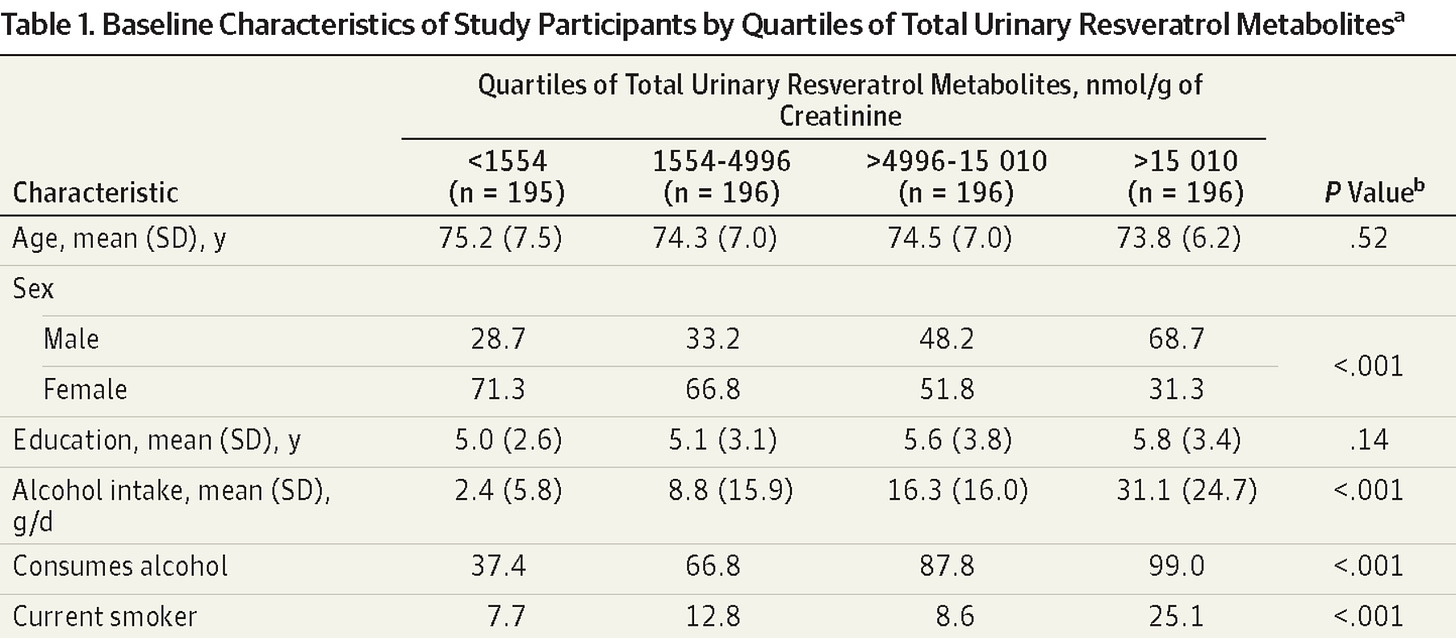

A colleague and I pulled up the full-text paper to read it more closely. At first it looked like a straightforward observational study. The participants were not taking resveratrol supplements, but rather getting their resveratrol from the diet. They didn’t measure resveratrol intake, but rather used the proxy of urinary resveratrol metabolites. They then grouped people by exposure level — in four quartile subgroups, representing those from least resveratrol to most resveratrol. They then examined cardiac risk factors and all-cause mortality… and found resveratrol metabolites weren’t associated with these.

As the headlines indicated, the participants with the highest resveratrol intake (as measured by urinary metabolites) were in no better health than those with the least. It turns out that promising supplement doesn’t work after all!

But, there was a major issue. Check out the table below.

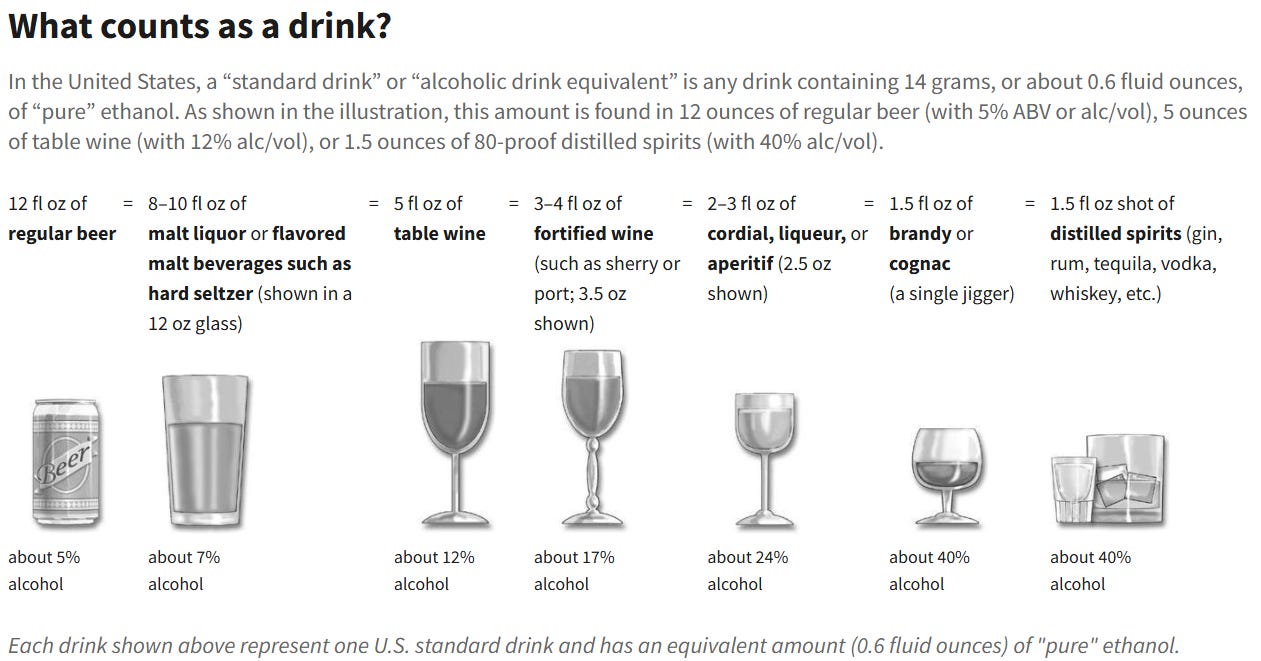

To land in the highest metabolite group (far right), participants had to be consuming a lot of wine. Not “a glass with dinner” levels. Substantially more. Like, the NIH definition of “heavy drinking” As shown below, a drink is considered 14 grams of alcohol. The “high resveratrol” group was getting >2 drinks per day, or 14+ drinks per week.

If that’s not enough, check out their smoking status. 25% of the high reseveratrol intake group were smokers.

Was anybody really expecting that the heavy drinking, smoking group would live longer or have a better cardiac profile than the group that drank 10x less, and had one third as many smokers? Of course not.

In other words, the “high resveratrol” group wasn’t a clean test of a dietary antioxidant. It was a group enriched for alcoholic smokers.

And then the study concluded that there was no cardiovascular benefit to dietary resveratrol. To be fair, the study did not claim to be studying supplments… But it did seemingly try to connect itself to supplements with language like: “Although annual sales of resveratrol supplements have reached $30 million in the United States alone, there is limited and conflicting human clinical data demonstrating any metabolic benefits of resveratrol…, and there are no data concerning… long-term supplementation in older people.”

That result wasn’t surprising at all. If anything, it would have been shocking to find a benefit. Heavy drinking and smoking are powerful cardiovascular risk factors. The logic suggesting resveratrol metabolites could give this population a biologic advantage over the lower quartile felt almost absurd.

Yet by that point the media narrative was already set. The nuance didn’t stand a chance against a simple headline. To most, it just showed resveratrol didn’t live up to the hype. No, this study didn’t look at resveratrol supplementation (which is what all of the laboratory animal studies and other promising human studies did). It essentially found that smoking and heavy drinking didn’t make you live longer, and somehow tied that into resveratrol.

We wrote another letter describing the issues with the study, in the hopes that the methodological nuance could provide greater context for interpreting the results. We explained the confounding, pointed out the interpretation issues, and tried to clarify what the study could and couldn’t actually say. Again, it was calm and methodical.

This one didn’t even get traction.

Rejected.

And that was it.

Not surprisingly, the original article kept accumulating citations and attention. Years later, it still pops up whenever someone wants to argue that red wine’s health benefits are overhyped. The same simplified takeaway keeps circulating, detached from the messy details of how the study was constructed.

I won’t go on a tangent about the French Paradox or dive into other resveratrol studies that have been published in the decade since. My point is that this was a serious issue that wasn’t fully addressed in this study, which limited the validity of the conclusions. It seemed worthy to put our comments on the record, so that journalists, scientists, and casual readers could understand the caveats. But, that important nuance didn’t matter to the journal.

Again, nothing corrected itself.

Were My Experiences The Exceptions? Or The Rule?

These are only two of the examples of my attempts to address issues in the literature. Sometimes a letter expressing doubt gets published — like it did for this other flawed, but popular resveratrol study. Other times, it doesn’t — like the letter I submitted regarding a recent paper on hormone therapy for transgender youth (described here).

A few years after my frustrations, Dr. David Allison published a fantastic piece in Nature describing his experiences attempting to correct errors in the literature. These are different than the examples I published above; he is specifically discussing statistical fallacies and numbers that didn’t add up. Let’s just say, his experience wasn’t good.

If you’ve read this far, I encourage you to read Dr. Allison’s piece - it is… shocking…

Some of the specific barriers they describe:

Journals were slow or unresponsive

One letter documenting a serious error took 11 months before the journal acted.

Even after acceptance, the correction and retraction still hadn’t been published.

Editors often seemed unsure how to handle problems

No clear process for submitting concerns.

Emails bounced around through “layers of ineffective correspondence.”

Authors sometimes refused to retract clearly flawed papers

Even when external statistical review confirmed a major analytic error, authors declined retraction.

Journals hesitated to override them.

Some journals charged money to publish corrections

Fees ranged from $1,700–$2,100 just to publish a letter pointing out someone else’s mistake.

In other words, researchers had to spend grant money to fix errors they didn’t create.

No standard mechanism exists to obtain raw data

Requests for data were often denied or ignored.

Without data, verifying or demonstrating errors became impossible.

Working cooperatively with authors often stalled things

In one case, authors promised to reanalyze data, which delayed formal correction for 10+ months.

The labor became unsustainable

After identifying dozens of substantial errors and pursuing 25+ corrections, they stopped.

Not because the problems were gone — because it consumed too much time.

Read the actual paper, there’s so much more than I present here.

Summary

I still teach evidence-based practice. I still believe in science as a way of understanding the world. And I do believe science can be self-correcting… but that is dependent on a constellation of stars aligning. People willing to put in the work, and editors willing to listen. And in the months-to-years the process takes, the flawed research continues to propogate through mainstream and social media without being addressed. Even when corrections do eventually happen, few pay attention.

Science isn’t self-correcting in the way we often imagine. It doesn’t automatically converge on the truth like a thermostat adjusting the temperature. It’s not like a self-driving vehicle navigating obstacles and adjusting speed and direction in real time.

Correction only happens when someone notices a problem, cares enough to investigate it, and invests substantial time persuading journal editors that it is worthy of public comment.

If any step in that chain fails, the error simply stays put.

Not because it’s correct.

Just because nobody fixed it.

If you like this kind of behind-the-scenes look at how science actually works, you might also enjoy my other newsletter, Academic Life, where I write more about the messy, human side of academia.

Tried to correct the literature yourself?

I’d genuinely like to hear how it went.

Really powerful point about how journals become gatekeepers of their own reputation rather than neutral truth-arbiters. The conflict of interest is so embedded that even when corrections are technically possible, the friction makes them practically unlikely. I ran into something similar when flagging methodological issues in a physiology paper once, the whole 'low priority' thing kinda forces you to let it go.

Science is absolutely NOT self-correcting. Journals - especially the high profile ones - are utterly loathe to publish any letters that point out serious issues that are plain to see. After all, both the editor and the reviewers should have noticed them. Things like checking whether the references say what the paper claims they say. Checking the basic logic of the arguments made in the paper. Or papers whose whole analysis is based on incorrectly using a method where the literature on the method makes it abundantly clear that that the method simply cannot be used that way. I could go on.

I have tried diligently to address numerous such issues and the journal editors not only did not accept the letters but did not even begin to address the issues. They just blow off letter writers.

So, when people say they don't trust science, sometimes they have good reason. Even when those people are themselves not particularly scientific. When we letter writers have especially strong arguments about problems with papers, the journals are especially resistant to admitting anything.

We can do so much better!

First step: Establish a mechanism by which the journals have an incentive to address errors in their papers. Some kind of reward to correcting problems and punishment for refusing to do so. Right now they have an incentive to cover them up. There is currently "free market" solution because the vast majority of readers and subscribers never realize how flawed some papers are.

NB - PubPeer can help some but it's not sufficient.