Evidence Isn’t Binary: What the NFL Teaches Us About Scientific Confidence

Why scientific evidence is probabilistic, imperfect, and always evolving—and why clinicians must learn to live in the middle

Quick clarification for new readers: This piece is about how we interpret scientific evidence, using the NFL as a metaphor. If you were hoping for a critique of the NFL’s own use—or misuse—of science, that’s a different body of work. I’ve written extensively on the NFL and injury risk elsewhere, including this article in Ars Technica.

One of the most persistent misunderstandings about science—among clinicians, journalists, policymakers, and even researchers themselves—is the belief that evidence is binary.

A study is either good or bad.

An intervention is either supported or unsupported.

A finding is either true or false.

That framing is intuitive. It’s also wrong.

Scientific evidence is not a light switch. It’s a continuum. For a more accurate mental model of how evidence actually works, the NFL offers a surprisingly good analogy.

The League, Not the Verdict: Why Evidence Isn’t Binary

In any given NFL season, there are elite teams, terrible teams, and a large, complicated middle.

Some teams dominate. Some are rebuilding. Most are neither.

A team that finishes 9–8 and misses the playoffs is not “bad.” It’s also not great. It likely has real strengths—maybe an excellent quarterback or defense—and real weaknesses—injuries, poor depth, inconsistent execution. That team might beat a Super Bowl contender one week and lose inexplicably the next.

That doesn’t mean the league is random. It means performance is probabilistic.

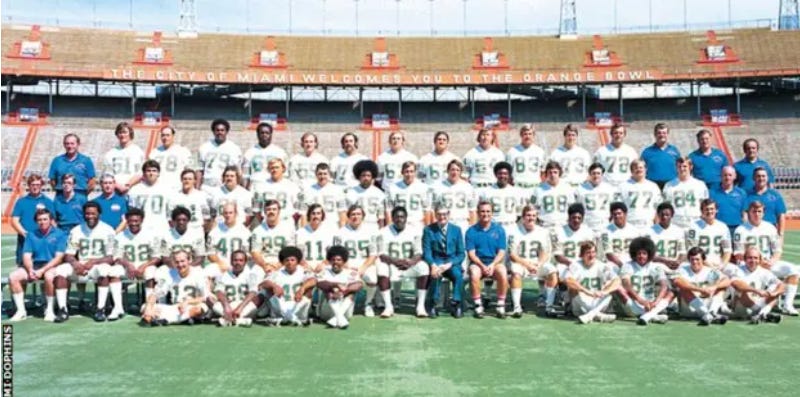

Even the best teams are not flawless. The 1972 Miami Dolphins, the only team to complete a perfect season, still threw interceptions, fumbled the ball, gave up points, and survived close games (see Week 6, in their 24-23 win over the Bills). Perfection at the season level didn’t require perfection at every play.

Science works the same way: high-quality evidence is not flawless, and flaws do not automatically make evidence untrustworthy.

No Paper Is Perfect

There is no such thing as a perfect research paper… or if a perfect study does exist, it is exceedingly rare… Some might even say, suspicious.

Every study has limitations—measurement error, bias, confounding, underpowered subgroups, imperfect outcomes, or analytical decisions that could reasonably have gone another way. There will be dropouts, short timeframes, and various assumptions—each of which can be called into question.

A high-quality study doesn’t mean flawless. It means the flaws are smaller, better understood, and less likely to overturn the main conclusion.

Just as great NFL teams will usually (but not always), beat terrible teams, stronger studies are more likely to be true—not guaranteed to be true. On the flip side, sometimes a bad team can defeat the reigning Super Bowl champion; and occasionally, a low-quality study will reveal a signal that survives more rigorous replication.

Not All Flaws Are Created Equal

Study quality tells us how much confidence we can place in a study’s results and conclusions—and that confidence exists on a continuum. Most studies can be critiqued if one looks hard enough, but not all critiques carry the same weight. Some limitations meaningfully threaten validity; others are worth noting but unlikely to change how the findings should be interpreted.

For example, how much does it matter if an a priori power analysis was not explicitly reported? That omission may be more concerning in a small or marginally powered study than in one with a large sample size and precise estimates. Were all possible confounders controlled for—or just the ones most plausibly related to the exposure and outcome? Was the statistical analysis appropriate but not ideal, or was it fundamentally incorrect? These distinctions matter. Treating every imperfection as equally disqualifying collapses meaningful differences in study quality and replaces judgment with box-checking.

The goal of critical appraisal is not to prove that a study is flawed—nearly all are—but to decide whether the flaws are minor, manageable, or fatal. That assessment, not the mere presence of limitations, is what determines how much confidence a study deserves.

Secondary Value Is Still Value

It’s important to note that this does not mean such papers are worthless, but rather that they are incapable of answering the specific question being asked. A clinical trial without a control group, for example, cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship for an intervention. It can, however, still provide useful information—such as whether the intervention appears well tolerated, whether serious adverse events occurred, or whether the study procedures are feasible. Likewise, even when effectiveness cannot be determined, such studies may offer valuable descriptive data, including the demographics of patients affected by a condition or patterns that help guide future, better-designed research.

Of course, that secondary value assumes the absence of rampant errors, research misconduct, or fraud. When those are present, it becomes difficult to trust ANY of the data.

When Flaws Are Fatal

But, a continuum doesn’t mean there’s no bottom.

Not all flaws are equal. A small sample size limits confidence. A broken outcome invalidates the result. Saying “all studies have flaws” should not be used to excuse studies that never had a chance to answer the question they posed. There’s a big difference between “weak scientific evidence” and “too scientifically unsound to interpret at all.”

Using our sport analogy, it’s theoretically possible that we could have a football team that isn’t merely bad—but structurally incapable of competing. A team without a quarterback, a kicker, or a defensive line isn’t just “rebuilding.” It’s not meaningfully playing the same game.

Science has equivalents. Some papers are fatally flawed. Not imperfect. Not early-stage. Fatally flawed.

These are studies with:

No valid comparison group

Outcomes that don’t measure what they claim

Designs that guarantee bias

Analyses that collapse under minimal scrutiny

Inappropriate statistical analysis

Selective reporting of data

Systemic errors or anomalies which erode trust

Researchers with a history of misconduct

These papers don’t sit at the bottom of the standings. They fail to meet the criteria to be ranked at all.

The Game Evolves… and So Do Evidence Standards

There’s another complication we often ignore: the standard for what counts as “high-quality” research changes over time.

We have better statistical tools now.

Better trial registration norms.

A deeper understanding of bias and causal inference.

Higher expectations for transparency, reproducibility, and analytic prespecification.

A study that was legitimately high quality thirty years ago may no longer meet today’s standards—not because it was careless or dishonest, but because the game has changed.

A perfect season: then vs. now

Football fans understand this intuitively. While the 1972 Miami Dolphins went undefeated, it’s hard to imagine that legendary team competing successfully against even the worst teams in today’s NFL, where players are bigger, faster, stronger, and where analytics and play design are vastly more sophisticated.

It’s also worth remembering that the 1972 season consisted of just 14 regular-season games, not the 17-game season teams face today. In other words, even the definition of a “perfect season” has changed. The New England Patriots actually won 18 consecutive games before losing the Super Bowl—an objectively longer winning streak than the celebrated Dolphins, yet one that is remembered very differently. Perfection, like dominance, is not a fixed standard; it is defined by the era, the rules, and the context in which it occurs.

That’s not an insult to the undefeated Dolphins. It’s a recognition of progress.

High-quality evidence: then vs. now

So in addition to evidence quality being continuous, it is also dynamic. What we once considered a “near-perfect” study may no longer meet modern expectations.

To make this more concrete, I revisited four articles published in the January 10, 1996 issue of JAMA (30 years ago from my time of writing) that span randomized trials, observational epidemiology, cross-sectional research, and meta-analysis. These included a randomized trial of atorvastatin for hypertriglyceridemia, a retrospective cohort study of post–Gulf War mortality among deployed US troops, a multicenter cross-sectional study of adolescents presenting for pregnancy testing, and a meta-analysis of outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. All four addressed clinically important questions, were methodologically thoughtful for their time, and appeared in one of the most selective medical journals in the world. None would reasonably be dismissed as “low quality,” and several remain widely cited today.

What stood out, however, were not fatal flaws—but missing elements that are now considered integral to high-quality research.

The randomized trial predated trial registration, CONSORT flow diagrams, and fully prespecified analytic hierarchies that are now routine; multiplicity was acknowledged, but not handled in the structured way modern readers would expect.

The observational Gulf War mortality study was careful and transparent, yet reflected an era before standardized reporting frameworks (e.g., STROBE) and before today’s more explicit causal-inference language and sensitivity analyses became commonplace.

The adolescent pregnancy testing study provided valuable descriptive insight, but would now likely be expected to provide clearer handling of missing data, stronger justification of representativeness, and more explicit analytic prespecification.

The pneumonia meta-analysis was especially illustrative: rigorous for its era, but clearly pre-PRISMA—lacking protocol registration, fully reproducible search strategies, standardized risk-of-bias assessment, and the structured transparency that now defines high-quality evidence synthesis.

In short, these papers were strong by the standards of their time, but many would require substantial modernization to meet today’s definition of “high quality.” That is not a criticism of the science—it is evidence that the bar has moved.

Some findings move up the standings as replication strengthens them.

Others slide downward as limitations become clearer—not necessarily because new studies disproved them, but because our expectations for rigor have changed.

In many cases, evidence is not replaced at all; it is reinterpreted in light of improved standards rather than overturned by superior experiments.

Science doesn’t “change its mind.”

It refines it.

When the Continuum Meets Institutions

While scientists generally understand this, institutions often behave as if evidence is binary and permanent.

Regulatory approvals are based on the best available evidence at the time—which is reasonable. Most regulatory frameworks also include mechanisms for post-approval surveillance and continuing review. In practice, however, those provisional judgments are often treated as durable credentials rather than hypotheses subject to routine re-evaluation. As a result, evidence can become functionally frozen, even as better methods emerge and stronger studies become possible.

Clinical guidelines can suffer similar inertia. Although most guidelines include formal processes for periodic review and updating, recommendations may nonetheless persist long after the evidentiary foundation has weakened—particularly when revisiting them is complex, controversial, or costly.

Marketing exploits this most aggressively. A single favorable study—sometimes early, sometimes fragile—is presented as definitive proof. Limitations vanish. Context disappears. The public is told: this works, not this worked under these conditions, with these uncertainties, at this moment in time.

That’s like handing out a championship banner in Week 3 and never checking the standings again.

The Clinician’s Dilemma

This dynamic creates a real problem in clinical practice.

Clinicians are taught to be “evidence-based practitioners,” but that phrase is often interpreted as binary: either there is evidence, or there isn’t. For those without deep training in research methods or statistics, the mere existence of studies with p-values <0.05 can feel like a green light.

Others—often after seeing the weaknesses laid bare—swing the opposite direction. They conclude there is “insufficient evidence” and ignore new findings entirely, waiting for some imagined threshold of perfection.

Both responses miss the point.

If clinicians waited for flawless evidence before acting, much of clinical practice would proceed in the absence of any evidence at all.

Evidence-based practice was never meant to be evidence-determined practice. Interpreting imperfect evidence is not a deviation from evidence-based care—it is the responsibility that evidence-based care demands. Evidence is an input, not a verdict.

Most clinical decisions live in the messy middle of the league:

where evidence exists but is incomplete,

where bias is present but not fatal,

where effects are uncertain but plausible,

and where patient values, cost, risk, and feasibility matter just as much as statistics.

The clinician’s responsibility is not to ask, “Is there evidence?”

It’s to ask, “Given the quality of this evidence, how much confidence should I place in it—and is that sufficient to influence my practice?”

A clinician may recognize that the evidence supporting an intervention is based on small trials with biased comparators and short follow-up—but also that the intervention is low-risk, inexpensive, and aligned with patient preferences. Using it cautiously, transparently, and without overstating benefit may be reasonable—even if the evidence is far from definitive.

That judgment will reasonably differ across clinicians and contexts. And that’s not a failure of evidence-based care. It is evidence-based care.

The Takeaway

Evidence is not a verdict.

It’s not a trophy.

It’s not a permanent credential.

It’s a position in the standings—earned relative to other studies, under the rules and tools of its time, and always subject to change.

Some studies are elite. Some are mediocre. Some shouldn’t be on the field at all. And over time, yesterday’s champions may be outmatched by today’s baseline competence.

That’s not chaos—that’s progressm provided we’re honest about it.

And honesty in science means resisting the urge to declare winners too early—and refusing to pretend the season is over when it clearly isn’t.

Where do you draw the line between “insufficient evidence” and “sufficient to cautiously inform practice”?

How do you weigh weak or biased evidence when the stakes are low—or when patients are asking for action anyway?

I’d especially welcome perspectives from clinicians, researchers, and guideline authors navigating this tension in real time.

This is such an important corrective! In medicine we often talk as if evidence is a light switch (“proven / not proven”), but at the bedside it’s almost always a dimmer: how big is the effect, how certain are we, and how well does this population map to this person in front of me?

What I appreciate in your framing is that it naturally pushes readers toward the questions that actually change decisions: What’s the absolute risk reduction (not just relative)? What’s the NNT/NNH? How fragile are the results (bias, missingness, multiplicity, selective reporting)? And what’s the prior plausibility + mechanistic coherence that makes the findings more or less likely to replicate?

Clinically, this is where shared decision-making becomes real, not “do we believe the study”, but “given imperfect evidence, what level of benefit would make this worth it for you, what harms are unacceptable, and what outcome do we actually care about (symptoms/function vs surrogate markers)?”

Medicine (and all fields of science) could use a better appreciation of levels of confidence. As a medical researcher, I've learned that the highest confidence evidence meets 6 criteria: Evidence that is repeatable, evidence that is obtained through prospective study, evidence obtained through more direct (not indirect) measurement, evidence obtained with minimal bias, evidence obtained with minimal assumptions, and studies summarized by reasonable claims (not claims that extend outside of the study parameters). Medicine generally has a strong appreciation of these criteria, demonstrated by the established levels of evidence in clinical medicine. Sadly, other fields of science have minimal appreciation of these concepts - a particular example is evolutionary biology.